Lecture 1.3

Introduction to Sleep Disorders

Sleep disorders may be associated with a variety of clinical symptoms that must be accurately assessed by the physician and the sleep technologist. These disorders must be differentiated from other states of altered physiological status, including normal sleep. This discussion of sleep disorders begins with a review of the eight major classifications of sleep disorders.

The field of clinical sleep medicine includes disorders that were previously in the domain of psychiatry, pulmonology, neurology, pediatrics, cardiology, and internal medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders was published by a committee of the AASM in 1990, and then revised in 1997. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders Diagnostic and Coding Manual, 2d ed. (ICSD-2), published in 2005, is the current comprehensive guide to classification of sleep disorders. As research has expanded knowledge surrounding sleep disorders and the field has become recognized in its own right, classifications have been revised, and work continues to integrate the sleep disorders into the current mainstream coding manuals for medical disorders, the ICD-9 and ICD-10.

The ICSD-2 sorts sleep disorders into eight categories:

Each category lists the specific sleep disorders that belong to that classification. For each disorder, the manual identifies the essential and associated features of the disorder and provides PSG findings and diagnostic criteria.

Sleep disorders specialists and sleep laboratories use ICSD-2 for correct coding of sleep problems, but we use a second classification on reports and bills to insurers. Insurance companies use the International Classification of Diseases 9 - Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to code medical problems including sleep disorders. The ICD is updated annually by national and international organizations; the next version, ICD-10, already has been adopted in most of the world outside the United States. The AASM provides a crosswalk between the sleep disorders listed in the ICSD-2 and the ICD-9-CM.

Insomnia is a disorder that causes difficulty falling asleep and/or staying asleep and that also affects daytime function. Adjustment insomnia, or acute insomnia, is associated with an identifiable life stress. Psychophysiological insomnia is characterized by anxiety about sleep. Idiopathic insomnia is not caused by any other illness and often begins in infancy or childhood. Inadequate sleep hygiene, such as excessive caffeine intake, also may cause insomnia. Insomnia may be associated with psychiatric disease, drug use, or other medical conditions.

Among the most common causes of insomnia, particularly in the elderly, is pain. Specifically, discomfort from arthritis, foot pain associated with diabetes, cluster headaches, angina, tumors, or ulcers may make sleep difficult.

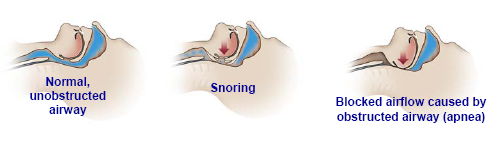

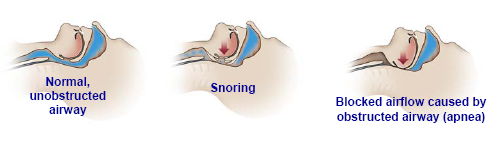

Sleep-disordered breathing may be due to an airway obstruction (obstructive sleep apnea), an abnormality in the part of the brain that controls respiration (central sleep apnea), or both (mixed sleep apnea). Sleep-related breathing disorders also include hypoventilation and hypoxemia syndromes.

There are several degrees of severity along a continuum of sleep-disordered breathing:

Snoring is an indication that there is a partial obstruction to the free flow of air, but patients may maintain normal flow volume, oxygen saturation, and sleep continuity by working harder to breathe.

A respiratory effort-related arousal (RERA) occurs when the increased breathing effort leads to a brief arousal from sleep, even without oxygen desaturation. Hypopnea consists of partial airway blockage with continuous respiratory effort and, by consensus definition, results in oxygen desaturation of 4 percent or more, or oxygen desaturation of at least 3 percent or an accompanying arousal. Apnea is the most severe of these events, resulting in complete airway blockage. An apneic event in adults is defined as cessation of airflow for ten seconds or more. Periods of apnea can occur in which breathing stops for ten seconds to a minute or so before resuming. The most recent recommendation in the ICSD-2 is to include apneas, hypopneas, and RERAs as part of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

Snoring is one of the cardinal signs of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) syndrome. Produced by the vibration of soft tissues in the upper airway, snoring varies in intensity and quality, depending on the time of night, the stage of sleep, body position, airflow rate, and the anatomical structure of the individual's nose and throat. Once thought to be a benign occurrence, snoring alone may lead to hypertension due to partial airway obstruction and nocturnal hypoventilation. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with higher risk of irregular heartbeat, high blood pressure, stroke, and heart attack. It occurs more often in patients who are male, obese, and elderly, but it may occur in patients who have none of those risk factors. Anatomic factors such as small jaw, large tongue, and large neck also increase the risk of obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea patients are usually advised to reduce their weight and avoid sedatives or hypnotic drugs and alcohol, especially at bedtime.

An obstructive apneic event is defined as the cessation of airflow due to a total obstruction of the airway occurring during sleep. As the patient sleeps, typically the jaw and tongue fall back, and the muscles relax at the back of the throat. There may be progressive narrowing of the air passage with each breath, until a complete blockage occurs. Respiratory effort usually persists or increases until the patient arouses to reestablish airway patency. Typically, repetitive dips in oxygen saturation levels occur in conjunction with the apneas, particularly in people who have underlying lung disease. The numerous arousals caused by the apneas result in fragmented sleep, which can lead in turn to excessive daytime sleepiness, a common symptom of sleep apnea. Few patients are aware of their nighttime respiratory difficulties. Frequently, the presenting complaints are of unrefreshing sleep, daytime sleepiness, daytime napping, and morning headaches. All of these are suggestive of sleep apnea.

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is an absence of airflow due to lack of diaphragmatic effort. Normal people have a small number of central apneas during sleep, often after turning over during a brief awakening. The polysomnogram may demonstrate a brief period when the patient does not breathe—essentially, this is a sigh. Central apneas may be frequent in normal people at high altitude and are often pathological in patients with congestive heart failure and neuropathology.

During an episode of central apnea, the problem is not an obstruction but rather a lack of effort to breathe. These patients often complain of insomnia, especially sleep onset insomnia; however, they may also complain of daytime hypersomnolence.

Nonobstructive (central) apnea alternating with periods of rapid breathing (hyperpnea) is called Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Cheyne-Stokes respiration can be due to lack of oxygen in the brain, low blood pH, or congestive heart failure. It may also be related to damage in areas of the brain involved with respiratory control, such as might occur with a stroke.

A mixed apneic event generally begins as a central apnea, often after a brief arousal. There is no effort to breathe for some seconds; then, as the patient's inspiratory muscles contract, there is no airflow because the airway is obstructed. In a mixed apnea, therefore, there are elements of central apnea and of obstructive apnea in the same event. As airflow cessation continues, oxygen saturation declines, respiratory effort continues to increase, and, finally, airflow is restored. Mixed apnea may be either more central or more obstructive in nature.

Idiopathic sleep-related nonobstructive alveolar hypoventilation syndrome occurs in patients with episodes of shallow breathing, desaturation, and arousal, without evidence of obstruction. Sleep-related hypoventilation and hypoxemia also may occur as a result of lung pathology, pulmonary vascular disorders, lower airway obstruction, neuromuscular diseases, or chest wall disorders such as severe scoliosis.

Narcolepsy and recurrent hypersomnia are disorders of excessive sleepiness. Hypersomnolence can be caused by numerous disorders including narcolepsy, apnea, sleep-disordered breathing, or periodic limb movements in sleep. One of the most common causes of hypersomnia is behaviorally induced insufficient sleep syndrome.

Narcolepsy is characterized by severe sleepiness, episodes of sudden weakness called cataplexy, sleep-onset hallucinations, sleep paralysis on wakening, and fragmented nocturnal sleep. Cataplexy is the name for brief periods of paralysis or loss of muscle tone while a person is awake, often brought on by excitement, anger, or laughing. The onset of narcolepsy usually occurs in adolescence or early adulthood, and it persists throughout life. Most patients have some, but not all, of these symptoms. Narcolepsy with cataplexy can be diagnosed clinically. Narcolepsy without cataplexy is diagnosed by the typical finding of multiple REM sleep periods during a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT).

In recent years scientists have discovered a new brain chemical, hypocretin, which helps control REM sleep. People with narcolepsy lack this chemical or have very low levels. Symptoms of narcolepsy are usually controlled by medications, including amphetamines and other stimulants, to promote alertness. A newer medication, sodium oxybate, is given to narcoleptics during sleep and improves sleepiness and cataplexy.

Patients who have severe sleepiness without cataplexy, and who do not have multiple REM periods on the MSLT, may be diagnosed with idiopathic hypersomnolence. In one type of idiopathic hypersomnolence, patients sleep at least ten hours daily and still are sleepy.

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders originate or develop from a misalignment between the person's sleep pattern and that which is desired or regarded as normal by society. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors may be involved in circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Conditions such as jet lag, shift work disorders, and delayed or advanced sleep phase syndromes are examples of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Patients with delayed sleep phase syndrome are often described as night owls—they are most comfortable going to sleep and waking much later than is socially acceptable. They may have insomnia if they go to bed at 11:00 p.m., for example, but fall asleep easily at 3:00 a.m. There is a genetic component to this disorder. A smaller number of patients have advanced sleep phase syndrome, resulting in early evening sleepiness and early morning awakening, which also has a genetic component.

Parasomnias consist of sleep disorders that are not abnormalities of the sleep process but are, instead, undesirable physical phenomena that occur during sleep. Disorders of arousal, partial arousal, and sleep-wake transition are all parasomnias. These disorders refer to episodic nocturnal events such as sleepwalking, sleep terrors, and confusional arousals. Sleep enuresis, nightmare disorder, REM sleep behavior disorder, and sleep-related eating disorder are also parasomnias.

Disorders of arousal from NREM sleep include confusional arousals, sleepwalking, and sleep terrors. Usually they occur during a partial arousal from delta sleep, or slow-wave sleep, in the first part of the night. Episodes often are more frequent in children and lessen in adults, but some adults still have frequent, bothersome, and potentially dangerous events. Patients often have family members with a history of similar disorders.

Parasomnias usually associated with REM sleep usually occur later in the night and include REM sleep behavior disorder, recurrent isolated sleep paralysis, and nightmare disorder. Patients with REM sleep behavior disorder appear to be acting out their dreams; for example, they may punch their bed partner and, when awakened, will report that they were dreaming of fighting. This disorder is more common in males, over the age of fifty, particularly with an underlying neurologic disorder such as Parkinson disease. Nightmare disorder is more common among children than adults but may occur at any age. When awakened from a nightmare patients are fully alert and report that they have been dreaming; in contrast, patients are difficult to awaken from an episode of night terrors and usually do not report having a dream.

Other parasomnias include sleep enuresis (bedwetting), sleep-related eating disorder, sleep-related groaning (catathrenia) and exploding head syndrome. Parasomnias may be observed in the sleep laboratory on any night, but patients are rarely referred for polysomnography primarily because of a parasomnia.

The movement disorders include periodic limb movement disorder, restless legs syndrome, bruxism, and sleep-related leg cramps. These disorders cause disrupted nighttime sleep and daytime sleepiness and fatigue.

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is described as an unpleasant deep, creeping, or crawling sensation in the calves that occurs more frequently near bedtime, and particularly when the individual is sitting or lying down. The abnormal sensation is relieved, at least temporarily, by movement. Occasional patients have similar symptoms in the arms, and some patients have daytime symptoms. Restless legs syndrome usually causes difficulty falling asleep. "Restless legs" are a symptom: the sleep specialist makes the diagnosis after interviewing the patient, and polysomnography is not generally performed. Most patients with RLS also have periodic limb movement disorder. About 10 percent of the population suffers from RLS, which often runs in families. Medications are generally used to treat RLS.

Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is not just a symptom but is an electromyographic abnormality occurring in sleep. It is defined as the occurrence of periodic episodes of repetitive and highly stereotyped leg jerks occurring during sleep. Periodic limb movement disorder occurs primarily in the legs and may cause difficulty maintaining sleep. About 80 percent of patients with RLS demonstrate PLMD on PSG testing; on the other hand, among patients with PLMD on polysomnography, only about 30 percent complain of RLS. The number of periodic limb movements varies greatly from night to night. Both PLMD and RLS may lead to significant sleep disturbances and sleep fragmentation, and often result in daytime sleepiness or insomnia.

Bruxism is involuntary tooth grinding or jaw clenching during sleep and occurs in about 10 percent of people. It is more common in children than adults. Bruxism may be diagnosed during polysomnography by the repetitive EMG artifact observed on the chin muscle channel or on channels referenced to the ear.

These symptoms are either on the borderline of normal versus abnormal sleep or are listed here because there is insufficient data to determine unequivocally that they are sleep disorders. These include the short sleeper or long sleeper (those individuals who have either a shorter or longer sleep episode than do most normal people), primary snoring, sleep talking, and several types of myoclonus or jerky movement during sleep.

This category currently comprises three classifications: Other Physiologic (Organic) Sleep Disorder, Other Sleep Disorder Not Due to Substance or Known Physiological Condition, and Environmental Sleep Disorder.

A disorder is temporarily placed in this category if the cause is not clear, but the expectation is that the disorder is based on physiologic or medical factors.

A disorder is placed in this category if it cannot be classified elsewhere in the ICSD-2 and there is a suggestion that the disorder is based on psychiatric or behavioral factors.

Environmental sleep disorder is also classified here. An environmental sleep disorder is a sleep disturbance caused by the environment, such as a disturbance related to noise, temperature, or other environmental disturbance that leads to daytime fatigue and sleepiness.

Sleep changes over the span of a lifetime, and some sleep disorders are more prevalent at certain ages. Some sleep disorders, for instance many parasomnias, are specific to or more common in the pediatric population, while some circadian rhythm disorders and insomnias are more prevalent in the elderly. In addition, some sleep disorders are gender specific, particularly related to the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause in women.

Some sleep disorders are specific to or primarily seen in the pediatric population. These include Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood (Sleep Onset Type), Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood (Limit Setting Type), Primary Sleep Apnea of Infancy, Congenital Central Alveolar Hypoventilation Syndrome, Sleep Related Rhythmic Movement Disorder, and Sleep Enuresis. Other pediatric sleep disorders are similar to adult disorders but are diagnosed based on specific pediatric criteria and are thus separated from the adult disorders. These disorders include Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Restless Legs Syndrome.

Polysomnography in pediatric patients requires specific expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of this particular population. Many sleep centers do not perform pediatric polysomnography; these patients are commonly referred to a sleep center with pediatric sleep medicine expertise.

The underlying causes of sleep disorders must be determined before they can be effectively treated. Polysomnography and MSLT have emerged as the standard laboratory tests for sleep disorders over the last thirty years and will help to diagnose many of the disorders covered in these notes. Some diagnoses, however, are made by the sleep specialist physician based on the patient's history and do not require sleep testing.