II. Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Sleep-disordered breathing may be due to an airway obstruction (obstructive sleep apnea), an abnormality in the part of the brain that controls respiration (central sleep apnea), or both (mixed sleep apnea). Sleep-related breathing disorders also include hypoventilation and hypoxemia syndromes.

There are several degrees of severity along a continuum of sleep-disordered breathing:

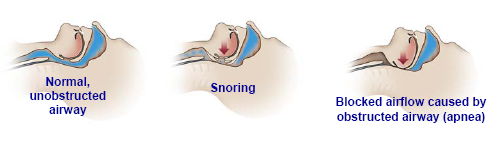

Snoring is an indication that there is a partial obstruction to the free flow of air, but patients may maintain normal flow volume, oxygen saturation, and sleep continuity by working harder to breathe.

A respiratory effort-related arousal (RERA) occurs when the increased breathing effort leads to a brief arousal from sleep, even without oxygen desaturation. Hypopnea consists of partial airway blockage with continuous respiratory effort and, by consensus definition, results in oxygen desaturation of 4 percent or more, or oxygen desaturation of at least 3 percent or an accompanying arousal. Apnea is the most severe of these events, resulting in complete airway blockage. An apneic event in adults is defined as cessation of airflow for ten seconds or more. Periods of apnea can occur in which breathing stops for ten seconds to a minute or so before resuming. The most recent recommendation in the ICSD-2 is to include apneas, hypopneas, and RERAs as part of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

Snoring is one of the cardinal signs of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) syndrome. Produced by the vibration of soft tissues in the upper airway, snoring varies in intensity and quality, depending on the time of night, the stage of sleep, body position, airflow rate, and the anatomical structure of the individual's nose and throat. Once thought to be a benign occurrence, snoring alone may lead to hypertension due to partial airway obstruction and nocturnal hypoventilation. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with higher risk of irregular heartbeat, high blood pressure, stroke, and heart attack. It occurs more often in patients who are male, obese, and elderly, but it may occur in patients who have none of those risk factors. Anatomic factors such as small jaw, large tongue, and large neck also increase the risk of obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea patients are usually advised to reduce their weight and avoid sedatives or hypnotic drugs and alcohol, especially at bedtime.

An obstructive apneic event is defined as the cessation of airflow due to a total obstruction of the airway occurring during sleep. As the patient sleeps, typically the jaw and tongue fall back, and the muscles relax at the back of the throat. There may be progressive narrowing of the air passage with each breath, until a complete blockage occurs. Respiratory effort usually persists or increases until the patient arouses to reestablish airway patency. Typically, repetitive dips in oxygen saturation levels occur in conjunction with the apneas, particularly in people who have underlying lung disease. The numerous arousals caused by the apneas result in fragmented sleep, which can lead in turn to excessive daytime sleepiness, a common symptom of sleep apnea. Few patients are aware of their nighttime respiratory difficulties. Frequently, the presenting complaints are of unrefreshing sleep, daytime sleepiness, daytime napping, and morning headaches. All of these are suggestive of sleep apnea.

Central Sleep Apnea

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is an absence of airflow due to lack of diaphragmatic effort. Normal people have a small number of central apneas during sleep, often after turning over during a brief awakening. The polysomnogram may demonstrate a brief period when the patient does not breathe—essentially, this is a sigh. Central apneas may be frequent in normal people at high altitude and are often pathological in patients with congestive heart failure and neuropathology.

During an episode of central apnea, the problem is not an obstruction but rather a lack of effort to breathe. These patients often complain of insomnia, especially sleep onset insomnia; however, they may also complain of daytime hypersomnolence.

Nonobstructive (central) apnea alternating with periods of rapid breathing (hyperpnea) is called Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Cheyne-Stokes respiration can be due to lack of oxygen in the brain, low blood pH, or congestive heart failure. It may also be related to damage in areas of the brain involved with respiratory control, such as might occur with a stroke.

Mixed Apnea

A mixed apneic event generally begins as a central apnea, often after a brief arousal. There is no effort to breathe for some seconds; then, as the patient's inspiratory muscles contract, there is no airflow because the airway is obstructed. In a mixed apnea, therefore, there are elements of central apnea and of obstructive apnea in the same event. As airflow cessation continues, oxygen saturation declines, respiratory effort continues to increase, and, finally, airflow is restored. Mixed apnea may be either more central or more obstructive in nature.

Alveolar Hypoventilation Syndrome

Idiopathic sleep-related nonobstructive alveolar hypoventilation syndrome occurs in patients with episodes of shallow breathing, desaturation, and arousal, without evidence of obstruction. Sleep-related hypoventilation and hypoxemia also may occur as a result of lung pathology, pulmonary vascular disorders, lower airway obstruction, neuromuscular diseases, or chest wall disorders such as severe scoliosis.